Marcel Studies,

Vol. 8, Issue No.1, 2023

Marcel’s Life-Work:

Some Archival Highlights for New Directions on a Bold Thinker

Jacob Saliba (Boston College)

When doing archival work, it is incredible how quickly you can surprise yourself with new information. Sometimes, you enter an archive and after ten minutes discover such an overwhelmingly thick archival trail that what began as one project soon transforms into five projects. The Marcel collections are no exception. Having returned from months of research on Marcel in France, I was delighted to have the opportunity to explore the Archive of the Gabriel Marcel Society in the United States. This is an online archive that is available, by request, to Marcel scholars. I will highlight here many of the strengths and unique qualities of this rich repository of material.

The Archive of the Gabriel Marcel Society contains a truly vibrant range of material beginning in the 1920s up to the 1970s. In it, there is a mighty blend of essays, lectures, correspondence, reviews, and even radio transcripts. The archived material reflects many of the major developments and evolutions in Marcel’s project, from his philosophical vision to his political views and religious ideas. In many respects, this material captures very well the deeper subtleties of Marcel’s project in the sense that he never had just “one project” but rather a whole mosaic of ideas and values that always seemed to move beyond a single, static position.

Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, Marcel’s work was preoccupied with idealism, Bergsonian philosophy, and Anglo-American pragmatism (to give just a few general categories). The archive provides material dealing with these themes; it includes some fragments and notes for The Metaphysical Journal, essays published in the prestigious Revue de métaphysique et de morale, and even writings for La Revue de jeunes, a lesser-known journal by today’s standards but an important venue for rising intellectual voices in France. What is perhaps most striking about the archive is not the fact that the collection contains these essays but rather that it also holds Marcel’s later “meta-reflections” on these earlier writings. Marcel was a very perceptive thinker and much of this comes forth in his ability to exercise self-critique. The archive captures effectively this two-way movement in Marcel’s thought.

In addition to the formative years of Marcel’s career in the 1920s and 1930s, the archive also preserves many of his timely essays on politics and culture that became very pronounced by the late 1930s and remained so until his death in 1973. The physical destruction and the moral catastrophe of the Second World War and Nazi occupation played heavy roles in the evolution of Marcel’s thought, in what we might call the “second half” of his career. Beyond the more well-known writings on technology, the archive has a superb blend of political essays and lectures on themes of communism, fascism, rearmament, and even suicide. More than this, you will find a thread of writings in which Marcel engages with the relationship between faith and politics, peace and ideology, sin and history, and prayer and society. Each of these writings helps to reveal a brilliant set of layers in Marcel’s thought over the course of many decades.

For example, in 1948, Marcel published an essay entitled “Pessimisme et conscience eschatologique” (“Pessimism and Eschatological Conscience”) in the journal Dieu Vivant. Written in the wake of World War II, the essay examines the ways in which the war’s devastation seemed to inflict a sense of final doom, “une imminent fin de ce que nous appelons le monde” (p. 119). This end, as Marcel observes, has inflicted a pessimistic outlook not only on ethical and political ideals but on Christian living and the trajectory of history itself. Marcel, therefore, attempted to invert this idea of an “end” from a negative into a positive, that is, from an end as an expiration of the world into an end as an occasion for new beginnings and resurrection. This idea of a “new beginning” or, at the very least, the attempt to transcend the negative mode of the category of “an end” had a deep resonance with many other lesser-known writings by Marcel from this period.

From the 1940s to the 1960s, Marcel deconstructed and rearranged certain categories of “finality,” “peace,” “tolerance,” “violence,” “propaganda,” and “immortality.” He even tried to produce a definition of “humanity” in which we understand ourselves not simply as humans living shoulder to shoulder by accident but rather as part of one, unified community in which we are driven purposefully and politically to be responsible for one another as an extension of ourselves. In this regard, older categories of “hope,” “faith,” and “vows” from his interwar writings come back to life in newer color and boldness. When seen all together, this material demonstrates insightful frameworks and intellectually subtle concepts at work in Marcel’s thought.

In addition to the political, religious, and philosophical writings, Marcel—as we are certainly aware today—was a prolific literary and theatre critic. He produced dozens upon dozens of reviews for the journal L’Europe Nouvelle. The archive holds these reviews on topics ranging from French reproductions of Aristophanes and Victor Hugo to more creative comparisons of St. Augustine with music and ballet. To be sure, not all of these reviews were glittering approvals. For scholars interested in seeing some of the really “critical” stances in Marcel’s literary and theatre criticism, those reviews exist, too. Furthermore, throughout his career, Marcel tried to identify pathways and connections between philosophy and theatre. Some of these essays never reached publication and, today, sit in the archive as drafts. Nevertheless, they are just as rich as any published writing by Marcel and may, in fact, help to reinterpret his published work.

Lastly, due to Marcel’s range of interests across many disciplines and venues, he corresponded with many other intellectuals of his time. The archive contains a set of letters with Albert Camus, W.E. Hocking, Aldous Huxley, and André Gide (to name just a few). The topics of their letters reflect philosophical concerns in absurdism, pragmatism, and logic as well as literary movements in modernism and symbolism. There are also transcripts of conferences where Marcel would provide responses to fellow Catholic philosophers, as was the case with his friend Étienne Gilson.

In many respects, the documents and writings in the Archive of the Gabriel Marcel Society resonates with material in the fonds Marcel held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. There, researchers and scholars will find hundreds of pages of transcripts from the Marcel soirees at his home on rue de Tournon, where he and friends discussed—and helped to create—the reception of German phenomenology in France. In addition, there is a vast collection of letters with French intellectuals and luminaries ranging from Raymond Aron, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir to Alexandre Koyré, Henri Bergson, and Maurice Blondel. There are even letters revealing a partnership between Marcel and Samuel Beckett to help young immigrant writers who after moving to Paris were eager to learn the latest styles in literary modernism. Marcel’s involvement with immigrant communities does not stop there. The French archive includes records of his work with academic and international organizations such as the Centre culturel islamique Centre catholique des intellectuels français, Centre de relations internationales culturelles, and the Centre de hautes études administratives sur l’Afrique et l’Asie modernes. These few examples only affirm that Marcel’s interests as a writer paralleled neatly with his wider convictions on and respect for the cosmopolitan changes in politics and culture throughout the twentieth century.

At present, we all have a certain level of familiarity with the “famous” texts of Marcel, his interventions into Catholic philosophy, his views of Sartre and Heidegger, his engagement with pragmatism, his critique of technology, and so forth. However, Marcel was a very dynamic thinker and hugely prolific writer, and this archival material shows that his range cannot and should not be limited to just his better-known themes. Based on material in the Archive of the Gabriel Marcel Society (along with the Marcel’s French-based archive in Paris), there are a certain number of avenues that can be taken to stretch and stimulate future scholarship.

Firstly, Marcel—especially after World War II—seemed to be developing a theory of politics and a philosophy of history beyond his critique of technological society. While much of this was driven by his Catholic convictions, it was also firmly grounded and empirically anchored in the political climate of the post-war era and the Cold War. Secondly, Marcel’s focus on the theatre and his insistence on its value for understanding the human condition seems to be further enriched by his way of integrating non-Catholic figures (e.g., Aristophanes, Gide, Hugo, etc.). Herein, scholars will find not only a certain attempt to diversify the Catholic tradition but also an interest in facilitating cross-cultural exchange—certainly an enduring political ideal for him. In fact, more than Catholic-secular cross-over, Marcel was also responsible for facilitating interreligious dialogues between Catholic and Jewish communities. (A lot of this can be seen in the archives in France, too.) Lastly, the Marcel Society’s collection seems to reveal a global turn in Marcel’s thinking, perhaps most apparent in his concept of “humanity.” With evidence from the Bibliothèque nationale de France, it is clear that Marcel was very committed to international politics and on certain occasions convened meetings with foreign delegations from around the world. In recent years, there has been a “global shift” in the humanities and Marcel’s work will certainly be one among those resources that bolden and enrich this new direction in the scholarship.

Ultimately, the Marcel collection is a resource for philosophers, intellectual historians, political theorists, and theologians alike. The non-systematic style of his thought, his democratic values, and his personal touch in articulating them were sources of strength for him. For us, today, they are occasions to continue unpacking the many untapped resources of his life’s work.

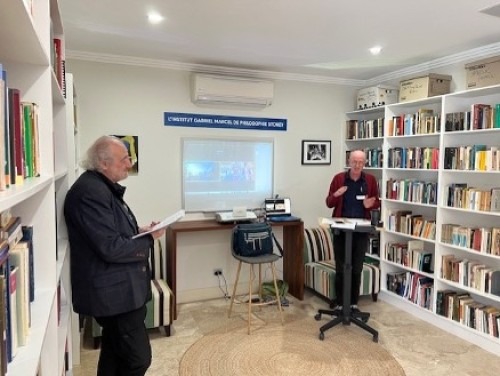

The Gabriel Marcel Institute of Philosophy (Sydney): Report on its Inaugural Conference, “T. S. Eliot and Religion”

It is my great pleasure to report on the inaugural conference of The Gabriel Marcel Institute of Philosophy, Sydney, Australia, on the theme of T. S. Eliot and Religion, held on Saturday, 28th October, 2023 (photos below). The inaugural conference was befitting in that it extended the spirit of Marcel’s fidelity to the past, as Eliot was one of his favorite poets. The four presentations discussed Eliot’s poetry and thought spanning a range of topics: a comparative study with Marcel; Eliot in relationship with the modern dilemma of a valueless life; to Eliot’s relationship with Christianity and other religions.

The keynote speaker, Professor Barry Spurr, presented “Poetics of the Incarnation: T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets.” Professor Spurr brought to light the importance of incarnational theology for Eliot’s poetry, as the Four Quartets express the imagery of the intersection of timelessness with time. For Eliot, the created order communicates the divine presence. The human person has the intrinsic capacity to cultivate this presence in intimate participation. The natural order facilitates the human person’s capacity to experience transcendence and divine love. Professor Spurr beautifully captured Eliot’s awareness of the importance of not cutting ourselves off from the created order (a theme also dear to Marcel).

Dr Raymond Younis presented “Through the unknown, remembered gate: Eliot and the Advent of Nihilism.” Dr Younis argued that Eliot’s response to nihilism has remained relatively under-researched. This profound presentation brought into dialogue the similarities between Eliot’s poetry and Marcel’s philosophical reflections, arguing that they both offer respective challenges to nihilism. Marcel’s paradoxical claims regarding inwardness, as that which reveals transcendence and value in being, can be read in conjunction with Eliot’s poetic sensibility.

Dr Matthew Del Nevo presented “Eliot in Eastern Perspective.” Dr Del Nevo began by stating some biographical facts about Eliot regarding his studies of Eastern religion, and then looked at some key parts of his most famous poems arguing that what we find there is not Christian, but more Indian or Buddhist. This presentation did not deny or make light of Eliot’s conversion to Christianity but argued that his Eastern influences worked in with it and were not effaced by it. However, Dr Del Nevo did argue that Eliot’s public and institutional self differed from his poetic persona, where his Eastern intuitions are evident.

Dr David Balosa joined us via Zoom and presented “A Common Interest: T. S. Eliot and Gabriel Marcel on Fostering Human Dignity.” Dr Balosa insightfully argued that the political implications of Eliot and Marcel’s conversion to Christianity and their shared interest in other cultures serve as a meaningful example for promoting human dignity across the globe and utilizing the political sphere in doing so. Dr Balosa elaborated on political themes in Marcel that may often be missed by readers.

The presentations were followed by an informal discussion and Q&A. The discussion revolved around similarities between Eliot and other poets such as Rilke (another favorite of Marcel). Papers based upon the presentations will be published in the first issue of our new journal, The Marcellian. On behalf of The Gabriel Marcel Institute, I wish to thank all friends of Marcel for your support in this newly established Institute, and a special word to the Marcel Society in the USA for promoting the legacy of Marcel across the USA and further abroad. Our intention down the road is to establish a more formal Marcel network in Australia.

Nathan Tartak, Director

ntartak.marcelinstitute@outlook.com

Image

Image

Image

October 2024 Sydney Conference:

Call for Papers (Deadline: Aug. 15th, 2024)

THOMAS MERTON AND RELIGION

Papers are welcome on any aspect of Thomas Merton and religion: possibilities may include Merton’s French Influence; Merton and St. John of the Cross; Merton and the Church Fathers; Merton’s spirituality; Merton’s poetry; Merton’s Asian Journal; Merton and Tao; Merton and Zen; Merton and Thomas Keating; Merton’s social activism; Merton’s vision of the church….or other aspects of Merton’s work that you have researched. A selection of papers will be published in The Marcellian, the journal of the conference and of the Institute.

Papers or queries to mdelnevo.marcelinstitute@outlook.com

All are welcome, in person or via Zoom.

Deadline for proposals: August 15, 2024. It is best to email Matthew Del Nevo (email above) to lodge a proposal and get a go-ahead. This is to ensure we have a miscellany of offerings and to keep a count of possible participants, in case we have too many. So try to get a proposal or paragraph of intent in as soon as possible.

Who can make a proposal? Seasoned academics or graduate students or freelance intellectuals, those in religious orders, etc. We are looking for new angles and critically interesting work on Merton, not accounts of things already well known.

Venue: The Gabriel Marcel Institute of Philosophy Sydney (or on Zoom), 44 Woodside Ave Strathfield, Sydney NSW 2135, Australia.

Date of Conference: Saturday, 26th Oct 2024, 11 am -5.00 pm (there is a chance the conference may extend from the Friday).

Cost: A$50. No cost for Members of Gabriel Marcel Society (USA) or to those giving papers.

Subscribe

Subscription to The Marcellian (paper copy) A$25. Purchase a back copy of last year’s inaugural conference and copy of The Marcellian issuing from the Conference on T. S. Eliot and Religion. Includes papers by Barry Spurr, Roger Kojecky and others.

Payment: You can pay in advance by PayPal using the email: Nathan Tartak ntartak.marcelinstitute@outlook.com marking the payment “Merton conference” or “subscription.” Remember if you subscribe to enclose a message on PayPal with your postal address. Email Nathan if you have any queries about payment methods.

WHAT MARCEL IS SAYING

On the Nature of the Thou

Image

People will say again, “But this distinction between the Thou and the He only applies to mental attitudes: it is phenomenological in the most exclusive sense of the word. Do you claim to give a metaphysical basis to this distinction, or a metaphysical validity to the Thou?”

The sense of the question is the really difficult thing to explain and elucidate. Let us try to state it more clearly, like this, for example. When I treat another as a Thou and no longer as a He, does this difference of treatment qualify me alone and my attitude to this other, or can I say that by treating him as a Thou I pierce more deeply into him and apprehend his being or his essence more directly?

Here again we must be careful. If by “piercing more deeply” or “apprehending his essence more directly,” we mean reaching a more exact knowledge, a knowledge that is in some sense more objective, then we must certainly reply “No.” In this respect, if we cling to a mode of objective definition, it will always be in our power to say that the Thou is an illusion. But notice that the term essence is itself extremely ambiguous; by essence we can understand either a nature or a freedom. It is perhaps of my essence qua freedom to be able to conform myself or not to my essence qua nature. It may be of my essence to be able not to be what I am; in plain words, to be able to betray myself. Essence qua nature is not what I reach in the Thou. In fact if I treat the Thou as a He, I reduce the other to being only nature; an animated object which works in some ways and not in others. If, on the contrary, I treat the other as Thou, I treat him and apprehend him qua freedom. I apprehend him qua freedom because he is also freedom, and is not only nature. What is more, I help him, in a sense, to be freed, I collaborate with his freedom. The formula sounds paradoxical and self-contradictory, but love is always proving it true. On the other hand, he is really other qua freedom; in fact qua nature he appears to me identical with what I am myself qua nature. On this side, no doubt, and only on this side, I can work on him by suggestion (there is an alarming and frequent confusion between the workings of love and the workings of suggestion).

…The other, in so far as he is other, only exists for me in so far as I am open to him, in so far as he is a Thou. But I am only open to him in so far as I cease to form a circle with myself, inside which I somehow place the other, or rather his idea; for inside this circle the other becomes the idea of the other, and the idea of the other is no longer the other qua other, but the other qua related to me; and in this condi¬tion he is uprooted and taken to bits, or at least in process of being taken to bits. [From Being and Having]

Taken from: Brendan Sweetman (editor), A Gabriel Marcel Reader (St. Augustine’s Press, 2011)

RECENT AND UPCOMING SCHOLARSHIP and notices

Image

1. PANDEMIC REFLECTIONS: Saint Francis and the lepers catch up with COVID (Ethics International, 2023). New book, edited by Geoffrey Karabin

In early 2020, we embarked on a shared and fractious journey through the COVID-19 pandemic. On this journey, St. Francis and the lepers' embrace took on living relevance in such questions as: What is one to make of an individual whose iconic act was to embrace those with a deadly and infectious disease? Does his example reveal something misguided in our reaction to the virus or does Francis offer a cautionary tale to be avoided? In the bluntest of terms, is Francis a religious fanatic and/or was our reaction to COVID-19 fanatical?

Such questions speak to the fecundity and perplexity of following Francis and taking his actions seriously. The pandemic provides an occasion to reconsider the meaning and legacy of Francis, while the example of Francis allows one to reflect upon the meaning and legacy of the contemporary response to the pandemic. Underlying both considerations is the question of how one ought to live and evaluate life during the pandemic.

2. PAUL MARCUS NEW BOOK, Just out!

Image

PSYCHOANALYSIS AND WISDOM: Encountering ‘Ethics of the Fathers’ (Routledge, 2024)

By Paul Marcus

Psychoanalysis and Wisdom applies psychoanalytic insights to one of the great examples of wisdom literature, the Ethics of the Fathers, an ethical tractate of the Talmud. This book will appeal to readers interested in psychoanalysis and psychotherapy and to academics and students of psychoanalytic studies, religious studies, Judaic studies, and philosophy.

“Paul Marcus has brought together a classic of wisdom literature, the Ethics of the Fathers, and psychoanalytic theory and practice in ways that mutually illuminate each other. Their co-nourishing interaction adds to our sense and feeling for life in depth and breadth. A welcome addition to our exploration of who we are and can be."—Michael Eigen, Ph. D; author of Contact with the Depths, Faith, and The Sensitive Self.

“Paul Marcus brings a unique psychoanalytic perspective to the ethical teachings of the ancient rabbis. Readers will discover a completely different way of looking at familiar statements in the Ethics of the Fathers. This volume succeeds in bringing to bear a modern discipline for understanding a classic Jewish text.”—Lawrence H. Schiffman, Global Distinguished Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University.

3. Brendan Sweetman Reference Article:

“Gabriel Marcel 1889-1973” in Nicolas de Warren and Ted Toadvine (eds.), Encyclopedia of Phenomenology (Springer, online, 2023).

Image

4. Coming soon:

Maria Traub, editor and translator, Toward Another Kingdom: Two Dramas of the Darker Years: Gabriel Marcel (forthcoming from St Augustine’s Press)

Professor Traub's latest translation of Gabriel Marcel's post-war plays is a window into the French philosopher's answer to his own signature questions regarding human existence. And as in the earlier collection of plays, The Invisible Threshold, the realism, passion and sincerity that frame conscience and moral duty in Marcel are most profoundly visible in the day-to-day of family life. Ideas never before presented theatrically emerge in Marcel's characters who struggle to understand their times and how best to live in them. Post-war life was as much a spiritual reckoning as it was a new society, and Marcel's treatment of introspection is a valuable key to his own work.

Marcel's dramas require characters to respond authentically and from their true selves. He thereby offers the vision of how individual compromises may build up to break the world and condemn, or, conversely, contribute to the discovery and meaning of relation and redemption. Traub's new translation will interest the player as much as the scholar, and Marcel's aptitude for theatrical writing is proven once again. His intellectual sensitivity creates characters that beckon performance, which is an added dimension to the presentation of the human condition.

5. Reminder…of our new book from St Augustine’s Press!

Image

The Invisible Threshold: Two Plays by Gabriel Marcel

Edited by Brendan Sweetman, Maria Traub, and Geoffrey Karabin; Translated by Maria Traub, 275 pages.

French philosopher and dramatist, Gabriel Marcel (1888-1973), who belonged to the movement of French existentialism, is one of the most insightful thinkers of the twentieth century. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Marcel approaches human existence from a theistic perspective, and gives priority to the themes of hope, fidelity and faith in the human search for meaning in a challenging world. Written early in his career, the plays in this new volume were originally published in 1913 under the title Le Seuil invisible (The Invisible Threshold).

The first play, Grace, explores the theme of religious conversion. The drama depicts a crisis between characters of genuine depth and sincerity, who are struggling with different interpretations of shared experiences. After a serious illness, Gerard, one of the main protagonists, undergoes a religious conversion, an experience which allows of two different and irreconcilable interpretations. The play raises the question of grace in a profound dramatization of a personal religious experience as it sustains in challenging life situations.

Similar themes are addressed but developed differently in The Sandcastle. This drama explores the confrontation between one’s beliefs and their consequences when faced with challenging family and social circumstances, especially with regard to the tension between love and freedom that often arises between parents and children. Marcel raises issues of moral character, commitment and sincerity, and introduces the role doubt plays in the way we form and hold our convictions. The springboard for the unfolding of the drama is the contrast between accepting Christianity in an intellectual and cultural sense, and a Christianity that is lived. Both plays bring out one of Marcel’s major themes: that life’s most profound, fulfilling experiences are often compromised in what he describes as the modern, broken world (le monde cassé), a world unfortunately characterized by alienation, loss of meaning and feelings of despair.

These new plays of Marcel’s, here translated into English for the first time, will appeal to all interested in the role of grace in everyday life, the relationship between faith and reason, the choice of faith in a secular world, and the struggle between inauthentic and authentic existence. Marcel raises weighty and challenging questions, but does not offer final answers. In his dramatic work, he leaves those to us.

Pope Francis, Marcel, and our contemporary times

Marcel is well known for his notions of disponibilité (a kind of “spiritual availability” to the other person), and the opposite attitude, indisponibilité. This idea, of course, carries clear echoes of the Christian theme of love thy neighbor, one of the reasons no doubt that Marcel’s work has always been of interest to Christians and Christian thinkers (see quoted passage from Marcel above). Similar themes are to be found in the work of Martin Buber, especially in his well-known distinction between I Thou and I It relationships. Although he does not mention Marcel by name, these themes are often found in the writings of Saint John Paul II.

It is no surprise then that we find an appeal to similar themes in the writings of Pope Francis! In fact, there is a direct reference to Marcel in the Pope’s Third Encyclical, Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship (published on October 3rd, 2020). In Chapter 3, Pope Francis makes reference to Marcel’s ideas in Creative Fidelity, actually quoting him on the subject of communication: “I communicate effectively with myself only insofar as I communicate with others.”

The encyclical emphasizes the biblical theme of care of the stranger, noting that when we come upon an injured stranger on the road we can assume one of two attitudes: we can pass by or we can stop to help. The type of person we are and the type of political, social or religious group we belong to will be defined by whether we include or exclude the injured stranger, the Pope notes. The US Conference of Catholic Bishops summarizes a main theme of the encyclical this way: “Faced with those injured by the shadows of a closed world and still lying by the roadside, we are invited by Pope Francis to make our own the world's desire for fraternity, starting with the recognition that we are ‘Fratelli tutti,’ brothers and sisters all.”

Within this context, it is no surprise that the Pope found affinity with Marcel’s thought. It is yet another reminder of the continuing relevance of Marcel’s profound understanding of the human person for our contemporary times.

Previous Editions: